Gerelee Odonchimed watched the 2018 Golden Globes with awe as actors wore all-black outfits in solidarity with victims of sexual harassment and abuse. For Odonchimed, a lawyer and gender equality advocate who watched the awards ceremony from her home in Mongolia, the sea of black gowns truly meant “Time’s Up.”

“This is important,” she says of Hollywood’s new movement to fight sexual assault, harassment, and inequality in the workplace. “Discussions on workplace harassment are finally being brought up.”

In 2012, well before #MeToo and #TimesUp took over the social media stratosphere, Odonchimed started working as vice director for education and advocacy at Women for Change — a prominent women’s empowerment organizations in Mongolia — to combat the victim blaming and shaming that allows sexual harassment and abuse to go on unchallenged.

About one in five women in Mongolia are victims of violence or assault and one in three women are victims of domestic violence. Odonchimed explains this abuse is often excused as a “regular thing” in Mongolian culture.

But time for excuses is running out. The #MeToo and #TimesUp movements have been silently surging in Mongolia for some time, according to Ganchimeg Namsrai, another women’s empowerment advocate and senior researcher at the Press Institute of Mongolia. Namsrai and Odonchimed — both participants in World Learning’s Leaders Advancing Democracy (LEAD) Mongolia program — are among Mongolia’s best-and-brightest emerging leaders. And they’re fighting for change.

Challenges women face in Mongolia

Justice has long been elusive for women in Mongolian society, where there’s a serious lack of information about sexual assault and domestic abuse — compounded by prevailing public misconceptions.

Domestic violence in particular has been a taboo subject across most of the country, where centuries of nomadic tradition tell families to handle their affairs without government interference. Government itself hasn’t always taken violence against women seriously: Mongolia’s penal code didn’t recognize domestic violence as a crime until 2016. And still, to this day, many law enforcement officials are not properly trained to enforce those regulations, nor does Mongolia consider domestic violence a human rights issue.

Even in the media, there’s little discussion of the legal consequences of gender-based violence. In fact, according to Namsrai, media coverage often reinforces negative stigmas against women who are victims of abuse. In 2017, she spent the year researching Mongolian media coverage of domestic violence, harassment, and gender equity.

So far, the results have not been assuring. “We found that at large, issues of gender equality are not covered fairly or in an informed, unbiased way in the media,” she says. “Gender bias and stigma bleed through.”

Namsrai’s research looks at articles and other media coverage of gender-based violence. She found that 70 percent of the article sources are male, and 70 percent of the photos are of men even though 91 percent of victims are women. Men are portrayed as businessmen or political figures, whereas women are portrayed as “instigators” or simply as housewives undeserving of sympathy. It’s highly sensationalized and meant to grab headlines. The same is true of media coverage of sexual assault and harassment, she says.

“Victim blaming is everywhere,” agrees Odonchimed. It’s never about the crime, but it’s instead about what the women said, what she wore, or that she might have done something wrong.

Through her own educational outreach and advocacy work, Odonchimed has discovered there is too little public understanding of gender-based violence and harassment as human rights issues. That misinformation leads to shaming and silence, which perpetuates the harassment and abuse as it keeps women from speaking up. As Namsrai explains, “They’re afraid of the stigma and what people will say, how they will be shamed.”

The good news is there is finally a conversation emerging, say Odonchimed and Namsrai. Women are becoming braver and beginning to speak out publicly.

Changing the narrative

The movement toward change is becoming more and more visible in Mongolia. Namsrai and Odonchimed are up-and-coming custodians of this emerging movement in Mongolia, ready to move forward as more women speak out and demand answers.

Indeed, Odonchimed and Women for Change have spent years working to address sexual harassment on the streets, at universities, and in the workplace, namely through educational initiatives and leadership programs with young women.

“We really want to raise awareness about sexual harassment,” says Odonchimed. She explains that women often don’t realize when and how they’re being harassed — too often she hears, “Oh, I didn’t know that was sexual harassment.” For Odonchimed, her work is about getting people to think about these issues as human rights issues by educating them at a very early age about human rights, human dignity and respect.

In 2017, Women for Change launched the “Behind Closed Doors” project, which set out to personalize domestic violence by setting up booths where people listened to real incidents of domestic violence. Those recordings — which included the sound of mother being struck while a child cried in the background — elicited a powerful emotional response.

Later that year, another national campaign launched to combat violence against women and children. In early November, the “Open Your Eyes” campaign was introduced to demand that the government galvanize its efforts and strengthen legal protections for women and children who are victims of violence and sexual assault. Though the government had adopted the Law to Combat Domestic Violence in 2016, the activists and demonstrators of Open Your Eyes are arguing that too many cases of abuse go unreported because of poor implementation of the law as well as societal resistance to acknowledge abuse as an issue.

Odonchimed cautions that addressing this issue is not simply about changing male behavior. It runs deeper than that. “This is a societal problem,” she says. “It’s a problem that affects everyone, men and women, and we as a society have to figure out how to fix it.”

As they watch these movements take root in Mongolian society, both Odonchimed and Namsrai are becoming more hopeful about their own work. Through their LEAD Mongolia experience, too — which brought them together with other young, emerging leaders from all sectors to learn, network and work on projects together — they have become much better connected with the larger advocacy community.

“I am optimistic [after my LEAD experience] because I now know that if strong and passionate people come together, we can really do a lot,” Namsrai says. For her, this group signifies the promise of transformation throughout Mongolian society.

“Change is possible in Mongolia,” says Odonchimed. “When I look at other young people and I see how their attitudes are changing for the better, I am proud to be with them. I feel like change is coming.”

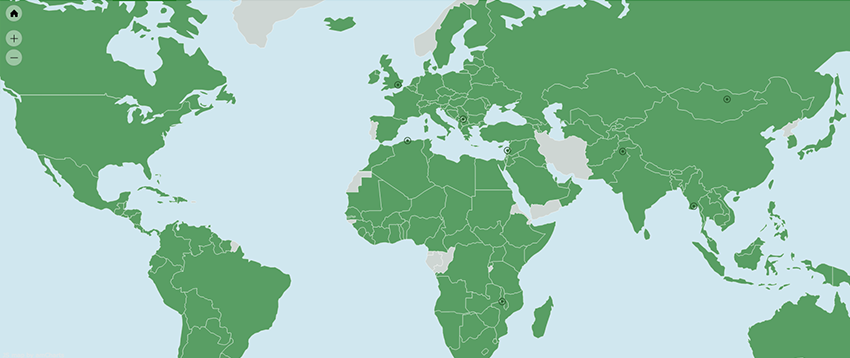

LEAD Mongolia is a World Learning program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which is working with some of Mongolia’s best and brightest emerging democracy advocates. LEAD Fellows represent all different sectors of society, but they have a common ambition to spur positive change on the issues they care about most.

Written by LEAD Mongolia Project Director Adam LeClair

Batnasan spent three weeks in the United States as part of the LEAD Mongolia program, run by World Learning and funded by USAID. He says his time in the U.S. allowed him to see how open and inclusive the country is toward people with disabilities.

Batnasan spent three weeks in the United States as part of the LEAD Mongolia program, run by World Learning and funded by USAID. He says his time in the U.S. allowed him to see how open and inclusive the country is toward people with disabilities. “World Learning’s mission is to be inclusive for everyone,” Berman says, adding that it’s important to make sure the needs of all participants are met during the planning process. “For this particular program, we helped connect the LEAD organizers with interpreting agencies and we connected them with the DC Deaf Community resources in order to make sure this program was 100% accessible.”

“World Learning’s mission is to be inclusive for everyone,” Berman says, adding that it’s important to make sure the needs of all participants are met during the planning process. “For this particular program, we helped connect the LEAD organizers with interpreting agencies and we connected them with the DC Deaf Community resources in order to make sure this program was 100% accessible.”

In late January more than

In late January more than