In April, the English Language Program in Myanmar was refitted for a new online summer initiative due to the coronavirus. But teachers in Yangon and Mandalay were concerned it would lack the appeal of their popular in-person programs.

The pandemic had abruptly shut down both American and Jefferson centers in mid-March leaving English-language instructors to quickly shift remaining lesson material online for the 344 students who were just weeks away from completing their term.

“Initially, students did not like the shift to virtual learning,” says Alyssa Moy, director of the English Language Program in Myanmar administered by World Learning. “They missed the camaraderie with fellow students and the fun, energetic teaching style of their instructors.” That was only one reason expectations for summer enrollment were low.

Limited Internet access and a lack of familiarity with online learning in Myanmar — an emerging Southeast Asian nation of 53 million people comprised of more than 100 ethnic groups — further complicate the situation.

Internet and mobile phones have been available in the country, formerly known as Burma, for less than five years, and the technology used for online learning is even newer to most people of Myanmar.

In a survey gauging interest in learning English online, only 100 people responded positively.

Moy says her team cautiously began planning for 80 participants as a result of initial feedback. So, they were blown away when almost 520 people pre-registered for the online summer English Language Program.

A second surprise: More than 450 of those who pre-registered had never signed up to participate in one of their programs.

Moy reports that over 110 people have taken the online placement test in advance of the May 7th launch.

She says the U.S. Embassy in Rangoon has been extremely supportive in advertising and promoting the new online English Language Program.

“This has certainly helped.”

The online term is two hours a day, five days a week over six weeks for a total of 60 hours of language instruction.

The cost to returning students is MMK 315,000 and MMK 325,000 for new students ($223-$230).

Similar to in-person English language classes, online courses will focus on the four primary language skills: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Students will also gain what World Learning refers to as “21st century skills.”

“Students will become more tech savvy, which will be useful for future learning since many universities overseas use similar online learning platforms,” Moy explains.

“Even within Myanmar, schools and companies have needed to move quickly to online platforms because of the pandemic.”

The majority of ELP students are high school and university age. English language levels vary, and the in-person program offers 10 levels. However, the new online version rolling out this month will offer levels 3–8.

Using the Moodle learning platform, the course structure includes synchronous — real time learning with the instructor — and asynchronous learning — off screen assignments and activities.

As they designed the program for online learning, Moy and her team sought the advice of World Learning Senior TESOL Specialist Radmila Popovic, who advised them to include additional asynchronous exercises.

Moy says, “This is definitely a shift from in-person learning, where there is constant interaction.”

What started as a crisis is increasingly viewed as an educational opportunity.

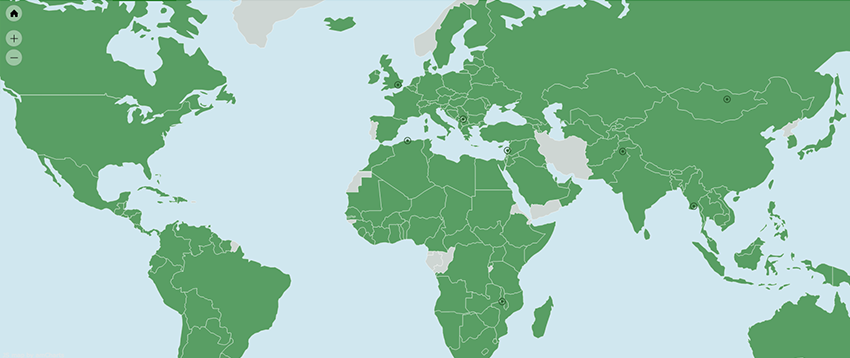

“We can serve not only a wider swath of Myanmar’s population, but these courses could also be offered in other countries around the world,” Moy added.

Why Mongolia?

Why Mongolia? Since early 2017, they’ve also gone on to share their experiences as changemakers with their peers across the region as part of the LEAD Alliance. LEAD Mongolia partnered with the International Republic Institute (IRI) to introduce the LEAD Alliance, in which LEAD Mongolia Fellows serve as mentors to other young emerging leaders in Bhutan, Kyrgyzstan, and Myanmar. LEAD Mongolia fellows help LEAD Alliance fellows implement projects in their countries. Fellows from both programs also gather for collaboration and networking at an annual summit in Ulaanbaatar.

Since early 2017, they’ve also gone on to share their experiences as changemakers with their peers across the region as part of the LEAD Alliance. LEAD Mongolia partnered with the International Republic Institute (IRI) to introduce the LEAD Alliance, in which LEAD Mongolia Fellows serve as mentors to other young emerging leaders in Bhutan, Kyrgyzstan, and Myanmar. LEAD Mongolia fellows help LEAD Alliance fellows implement projects in their countries. Fellows from both programs also gather for collaboration and networking at an annual summit in Ulaanbaatar.